|

You are a "nervous" Melancholic, with an

abundance of black bile. Melancholics are characterized by the element of Earth, the season of Autumn,

middle-aged adulthood, the colors black and blue,

Saturn, and the characteristics of "Cold"

and "Dry." Animals used to symbolize the Melancholic include

the pig, cat, and owl. To enhance your Melancholic tendencies, listen to

music in the Mixolydian Mode; to diminish those tendencies, listen to music

in the Hypomixolydian mode.

Famous Melancholics include St. John of the Cross, St. John the Divine,

St. Francis, and St. Catherine of Siena.

If you were living in the Age of Faith, perfect career choices for you would be contemplative religious, theologian, artist, or

writer.

From "The Four Temperaments," by Rev. Conrad Hock:

The Melancholic:

- Is self-conscious, easily

embarrassed, timid, and bashful.

- Avoids talking before a group;

when obliged to he finds it difficult.

- Prefers to work and play alone.

Good in details; careful.

- Is deliberative; slow in making

decisions; perhaps overcautious even in minor matters.

- Is lacking in self-confidence

and initiative; compliant and yielding.

- Tends to detachment from

environment; reserved and distant except to intimate friends.

- Tends to depression; frequently

moody or gloomy; very sensitive; easily hurt.

- Does not form acquaintances

readily; prefers narrow range of friends; tends to exclude others.

- Worries over possible

misfortune; crosses bridges before coming to them.

- Is secretive; seclusive; shut

in; not inclined to speak unless spoken to.

- Is slow in movement;

deliberative or perhaps indecisive; moods frequent and constant.

- Is often represents himself at a

disadvantage; modest and unassuming.

The melancholic person is but feebly

excited by whatever acts upon him. The reaction is weak, but this feeble

impression remains for a long time and by subsequent similar impressions

grows stronger and at last excites the mind so vehemently that it is

difficult to eradicate it.

Such impression may be compared to a post, which by repeated strokes is

driven deeper and deeper into the ground, so that at last it is hardly

possible to pull it out again. This propensity of the melancholic needs

special attention. It serves as a key to solve the many riddles in his

behavior.

II FUNDAMENTAL DISPOSITION OF THE MELANCHOLIC

1. Inclination to reflection. The thinking of the melancholic easily turns

into reflection. The thoughts of the melancholic are far reaching. He dwells

with pleasure upon the past and is preoccupied by occurrences of the long

ago; he is penetrating; is not satisfied with the superficial, searches for

the cause and correlation of things; seeks the laws which affect human life,

the principles according to which man should act. His thoughts are of a wide

range; he looks ahead into the future; ascends to the eternal. The

melancholic is of an extremely soft-hearted disposition. His very thoughts

arouse his own sympathy and are accompanied by a mysterious longing. Often

they stir him up profoundly, particularly religious reflections or plans

which he cherishes; yet he hardly permits his fierce excitement to be noticed

outwardly. The untrained melancholic is easily given to brooding and to

day-dreaming.

2. Love of retirement. The melancholic does not feel at home among a crowd

for any length of time; he loves silence and solitude. Being inclined to

introspection he secludes himself from the crowds, forgets his environment,

and makes poor use of his senses — eyes, ears, etc. In company he is often

distracted, because he is absorbed by his own thoughts. By reason of his lack

of observation and his dreaming the melancholic person has many a mishap in

his daily life and at his work.

3. Serious conception of life. The melancholic looks at life always from the

serious side. At the core of his heart there is always a certain sadness, 'a

weeping of the heart,' not because the melancholic is sick or morbid, as many

claim, but because he is permeated with a strong longing for an ultimate good

(God) and eternity, and feels continually hampered by earthly and temporal

affairs and impeded in his cravings. The melancholic is a stranger here below

and feels homesick for God and eternity.

4. Inclination to passivity. The melancholic is a passive temperament. The

person possessing such a temperament, therefore, has not the vivacious,

quick, progressive, active propensity, of the choleric or sanguine, but is

slow, pensive, reflective. It is difficult to move him to quick action, since

he has a marked inclination to passivity and inactivity. This pensive

propensity of the melancholic accounts for his fear of suffering and

difficulties as well as for his dread of interior exertion and

self-denial.

III PECULIARITIES OF THE MELANCHOLIC

1. He is reserved. He finds it difficult to form new acquaintances and speaks

little among strangers. He reveals his inmost thoughts reluctantly and only

to those whom he trusts. He does not easily find the right word to express

and describe his sentiments. He yearns often to express himself, because it

affords him real relief, to confide the sad, depressing thoughts which burden

his heart to a person who sympathizes with him. On the other hand, it

requires great exertion on his part to manifest himself, and, when he does

so, he goes about it so awkwardly that he does not feel satisfied and finds

no rest. Such experiences tend to make the melancholic more reserved. A

teacher of melancholic pupils, therefore, must he aware of these

peculiarities and must take them into consideration; otherwise he will do a

great deal of harm to his charges.

Confession is a great burden to the melancholic, while it is comparatively

easy to the sanguine. The melancholic wants to manifest himself, but cannot;

the choleric can express himself easily, but does not want to.

2. The melancholic is irresolute. On account of too many considerations and

too much fear of difficulties and of the possibility that his plans or works

may fail, the melancholic can hardly reach a decision. He is inclined to

defer his decision. What he could do today he postpones for tomorrow, the day

after tomorrow, or even for the next week. Then he forgets about it and thus

it happens that what he could have done in an hour takes weeks and months. He

is never finished. For many a. melancholic person it may take a long time to

decide about his vocation to the religious life. The melancholic is a man of

missed opportunities. While he sees that others have crossed the creek long

ago, he still deliberates whether he too should and can jump over it. Because

the melancholic discovers many ways by his reflection and has difficulties in

deciding which one to take, he easily gives way to others, and does not

stubbornly insist on his own opinion.

3. The melancholic is despondent and without courage. He is pusillanimous and

timid if he is called upon to begin a new work, to execute a disagreeable

task, to venture on a new undertaking. He has a strong will coupled with

talent and power, but no courage. It has become proverbial therefore:

"Throw the melancholic into the water and he will learn to swim."

If difficulties in his undertakings are encountered by the melancholic, even

if they are only very insignificant, he feels discouraged and is tempted to

give up the ship, instead of conquering the obstacle and repairing the ill

success by increased effort.

4. The melancholic is slow and awkward.

a) He is slow in his thinking. He feels it necessary, first of all, to

consider and reconsider everything until he can form a calm and safe

judgment.

b) He is slow in his speech. If he is called upon to answer quickly or to

speak without preparation, or if he fears that too much depends on his

answer, he becomes restless and does not find the right word and consequently

often makes a false and unsatisfactory reply. This slow thinking may be the

reason why the melancholic often stutters, leaves his sentences incomplete,

uses wrong phrases, or searches for the right expression. He is also slow,

not lazy, at his work. He works carefully and reliably, but only if he has

ample time and is not pressed. He himself naturally does not believe that he

is a slow worker.

5. The pride of the melancholic has its very peculiar side. He does not seek

honor or recognition; on the contrary, he is loathe to appear in public and

to be praised. But he is very much afraid of disgrace and humiliation. He

often displays great reserve and thereby gives the impression of modesty and

humility; in reality he retires only because he is afraid of being put to

shame. He allows others to be preferred to him, even if they are less

qualified and capable than himself for the particular work, position, or

office, but at the same time he feels slighted because he is being ignored

and his talents are not appreciated.

The melancholic person, if he really wishes to become perfect, must pay very

close attention to these feelings of resentment and excessive sensitiveness

in the face of even small humiliations.

From what has been said so far, it is evident that it is difficult to deal

with melancholic persons. Because of their peculiarities they are frequently

misjudged and treated wrongly. The melancholic feels keenly and therefore

retires and secludes himself. Also, the melancholic has few friends, because

few understand him and because he takes few into his confidence.

IV BRIGHT SIDE OF THE MELANCHOLIC TEMPERAMENT

1. The melancholic practices with ease and joy interior prayer. His serious

view of life, his love of solitude, and his inclination to reflection are a

great help to him in acquiring the interior life of prayer. He has, as it

were, a natural inclination to piety. Meditating on the perishable things of

this world he thinks of the eternal; sojourning on earth he is attracted to

Heaven. Many saints were of a melancholic temperament. This temperament

causes difficulties at prayer, since the melancholic person easily loses

courage in trials and sufferings and consequently lacks confidence in God, in

his prayers, and can be very much distracted by pusillanimous and sad thoughts.

2. In communication with God the melancholic finds a deep and indescribable

peace.

He, better than anyone else, understands the words of St. Augustine:

"Thee, O Lord, have created us for yourself, and our heart finds no

rest, until it rests in Thee." His heart, so capable of strong

affections and lofty sentiments, finds perfect peace in communion with God.

This peace of heart he also feels in his sufferings, if he only preserves his

confidence in God and his love for the Crucified.

3. The melancholic is often a great benefactor to his fellow men. He guides

others to God, is a good counselor in difficulties, and a prudent,

trustworthy, and well-meaning superior. He has great sympathy with his fellow

men and a keen desire to help them. If the confidence in God supports the

melancholic and encourages him to action, he is willing to make great

sacrifices for his neighbor and is strong and unshakable in the battle for

ideals. Schubert, in his Psychology, says of the melancholic nature: "It

has been the prevailing mental disposition of the most sublime poets,

artists, of the most profound thinkers, the greatest inventors, legislators,

and especially of those spiritual giants who at their time made known to

their nations the entrance to a higher and blissful world of the Divine, to

which they themselves were carried by an insatiable longing."

V DARK SIDE OF THE MELANCHOLIC TEMPERAMENT

1. The melancholic by committing sin falls into the most terrible distress of

mind, because in the depth of his heart he is, more than those of other

temperaments, filled with a longing desire for God, with a keen perception of

the malice and consequences of sin. The consciousness of being separated from

God by mortal sin has a crushing effect upon him. If he falls into grievous

sin, it is hard for him to rise again, because confession, in which he is

bound to humiliate himself deeply, is so hard for him. He is also in great

danger of falling back into sin; because by his continual brooding over the

sins committed he causes new temptations to arise. When tempted he indulges

in sentimental moods, thus increasing the danger and the strength of

temptations. To remain in a state of sin or even occasionally to relapse into

sin may cause him a profound and lasting sadness, and rob him gradually of

confidence in God and in himself. He says to himself: "I have not the

strength to rise again and God does not help me either by His grace, for He

does not love me but wants to damn me." This fatal condition can easily

assume the proportion of despair.

2. A melancholic person who has no confidence in God and love for the Cross

falls into great despondency, inactivity, and even into despair.

If he has confidence in God and love for the Crucified, he is led to God and

sanctified more quickly by suffering mishaps, calumniation, unfair treatment,

etc. But if these two virtues are lacking, his condition is very dangerous

and pitiable. If sufferings, although little in themselves, befall him, the

melancholic person, who has no confidence in God and love for Christ, becomes

downcast and depressed, ill-humored and sensitive. He does not speak, or he

speaks very little, is peevish and disconsolate and keeps apart from his

fellow men. Soon he loses courage to continue his work, and interest even in

his professional occupation.

He feels that he has nothing but sorrow and grief. Finally this disposition

may culminate in actual despondency and despair.

3. The melancholic who gives way to sad moods, falls into many faults against

charity and becomes a real burden to his fellow men.

a) He easily loses confidence in his fellow men, (especially Superiors,

Confessors), because of slight defects which he discovers in them, or on

account of corrections in small matters.

b) He is vehemently exasperated and provoked by disorder or injustice. The

cause of his exasperation is often justifiable, but rarely to the degree

felt.

c) He can hardly forgive offences. The first offense he ignores quite easily.

But renewed offenses penetrate deeply into the soul and can hardly be

forgotten. Strong aversion easily takes root in his heart against persons

from whom he has suffered, or in whom he finds this or that fault. This

aversion becomes so strong that he can hardly see these persons without new

excitement, that he does not want to speak to them and is exasperated by the

very thought of them. Usually this aversion is abandoned only after the

melancholic is separated from persons who incurred his displeasure and at

times only after months or even years.

d) He is very suspicious. He rarely trusts people and is always afraid that

others have a grudge against him. Thus he often and without cause entertains

uncharitable and unjust suspicion about his neighbor, conjectures evil

intentions, and fears dangers which do not exist at all.

e) He sees everything from the dark side. He is peevish, always draws

attention to the serious side of affairs, complains regularly about the

perversion of people, bad times, downfall of morals, etc. His motto is:

things grow worse all along. Offenses, mishaps, obstacles he always considers

much worse than they really are. The consequence is often excessive sadness,

unfounded vexation about others, brooding for weeks and weeks on account of

real or imaginary insults. Melancholic persons who give way to this

disposition to look at everything through a dark glass, gradually become

pessimists, that is, persons who always expect a bad result; hypochondriacs,

that is, persons who complain continually of insignificant ailments and

constantly fear grave sickness; misanthropes, that is, persons who suffer

from fear and hatred of men.

f) He finds peculiar difficulties in correcting people. As said above he is

vehemently excited at the slightest disorder or injustice and feels obliged

to correct such disorders, but at the same time he has very little skill or

courage in making corrections. He deliberates long on how to express the

correction; but when he is about to make it, the words fail him, or he goes

about it so carefully, so tenderly and reluctantly that it can hardly be

called a correction.

If the melancholic tries to master his timidity, he easily falls into the

opposite fault of shouting his correction excitedly, angrily, in unsuited or

scolding words, so that again his reproach loses its effect. This difficulty

is the besetting cross of melancholic superiors. They are unable to discuss

things with others, therefore, they swallow their grief and permit many

disorders to creep in, although their conscience recognizes the duty to

interfere. Melancholic educators, too, often commit the fault of keeping

silent too long about a fault of their charges and when at last they are

forced to speak, they do it in such an unfortunate and harsh manner, that the

pupils become discouraged and frightened by such admonitions, instead of

being encouraged and directed.

VI METHOD OF SELF-TRAINING FOR THE MELANCHOLIC PERSON

1. The melancholic must cultivate great confidence in God and love for

suffering, for his spiritual and temporal welfare depend on these two

virtues. Confidence in God and love of the Crucified are the two pillars on

which he will rest so firmly, that he will not succumb to the most severe

trials arising from his temperament. The misfortune of the melancholic

consists in refusing to carry his cross; his salvation will be found in the

voluntary and joyful bearing of that cross. Therefore, he should meditate

often on the Providence of God, and the goodness of the Heavenly Father, who

sends sufferings only for our spiritual welfare, and he must practice a

fervent devotion to the Passion of Christ and His Sorrowful Mother

Mary.

2. He should always, especially during attacks of melancholy, say to himself:

''It is not so bad as I imagine. I see things too darkly," or "I am

a pessimist."

3. He must from the very beginning resist every feeling of aversion,

diffidence, discouragement, or despondency, so that these evil impressions

can take no root in the soul.

4. He must keep himself continually occupied, so that he finds no time for

brooding. Persevering work will master all.

5. He is bound to cultivate the good side of his temperament and especially

his inclination to interior life and his sympathy for suffering fellow men.

He must struggle continually against his weaknesses.

6. St. Theresa devotes an entire chapter to the treatment of malicious

melancholics. She writes: "Upon close observation you will notice that

melancholic persons are especially inclined to have their own way, to say

everything that comes into their mind, to watch for the faults of others in

order to hide their own and to find peace in that which is according to their

own liking." St. Theresa, in this chapter touches upon two points to

which the melancholic person must pay special attention. He frequently is

much excited, full of disgust and bitterness, because he occupies himself too

much with the faults of others, and again because he would like to have

everything according to his own will and notion.

He can get into bad humor and discouragement on account of the most

insignificant things. If he feels very downcast he should ask himself whether

he concerned himself too much about the faults of others. Let other people

have their own way! Or whether perhaps things do not go according to his own

will. Let him learn the truth of the words of the Imitation (I, 22),

"Who is there that has all things according to his will? Neither I nor

you, nor any man on earth. There is no man in the world without some trouble

or affliction be he king or pope. Who then is the best off? Truly he that is

able to suffer something for the love of God."

VII IMPORTANT POINTS IN THE TRAINING OF THE MELANCHOLIC

In the treatment of the melancholic special attention must be given to the

following points:

1. It is necessary to have a sympathetic understanding of the melancholic. In

his entire deportment he presents many riddles to those who do not understand

the peculiarities of the melancholic temperament. It is necessary, therefore,

to study it and at the same time to find out how this temperament manifests

itself in each individual. Without this knowledge great mistakes cannot be

avoided.

2. It is necessary to gain the confidence of the melancholic person. This is

not at all easy and can be done only by giving him a good example in

everything and by manifesting an unselfish and sincere love for him. Like an

unfolding bud opens to the sun, so the heart of the melancholic person opens

to the sunshine of kindness and love.

3. One must always encourage him. Rude reproach, harsh treatment, hardness of

heart cast him down and paralyze his efforts. Friendly advice and patience

with his slow actions give him courage and vigor. He will show himself very

grateful for such kindness.

4. It is well to keep him always busy, but do not overburden him with

work.

5. Because melancholics take everything to heart and are very sensitive, they

are in great danger of weakening their nerves. It is necessary, therefore, to

watch nervous troubles of those entrusted to one's care. Melancholics who

suffer a nervous breakdown are in a very bad state and cannot recover very

easily.

6. In the training of a melancholic child, special care must be taken to be

always kind and friendly, to encourage and keep him busy. The child,

moreover, must be taught always to pronounce words properly, to use his five

senses, and to cultivate piety. Special care must be observed in the

punishment of the melancholic child, otherwise obstinacy and excessive

reserve may result. Necessary punishment must be given with precaution and

great kindness and the slightest appearance of injustice must be carefully

avoided.

|

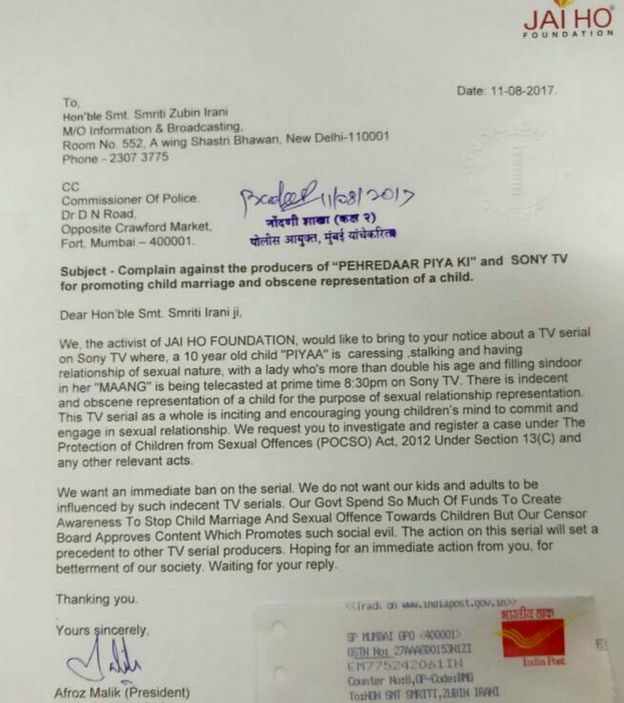

SONY TV

SONY TV SONY TV

SONY TV