Slobodan Simić lounged on the crude

wooden bench in Zasavica Special Nature Reserve’s dining room like the

caterpillar from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, holding court and

puffing on the quarter-bent Calabash-style briar pipe that dangled

delicately from his teeth. Tanned creases ran down his face like

tributaries, and his eyes sparkled with mischief.

“Rakia?” he said, offering me a shot of the strong Balkan brandy that is often drunk in the morning, even before coffee.

“Ne, hvala,” I replied, shaking my head and thanking him. Instead, I accepted a cup of thick Turkish coffee accompanied by a shot glass of donkey milk from Zasavica’s herd. It was my first time tasting the sweet milk; I was even more eager to try the donkey cheese, a delicacy I’d learned about a few years back when rumours swirled that Serbian tennis ace Novak Djokovic was buying up their entire stock for his restaurants. Although the rumours were untrue, they brought global attention to Zasavica – and Serbia.

Despite being a nature lover, Simić never set out to create a farm. Twenty years ago, the former MP-turned-conservationist remembered that he’d heard about some wetlands in west-central Serbia. His ex-wife’s parents, who lived in a nearby village, took him to see them.

“I fell in love immediately,” he said.

Zasavica, named after the river that runs through it, is located just 90km northwest of Belgrade, but the 1,825-hectare area was virtually undiscovered. The place is ripe for bird watching, and in the summer, hues are so vibrant they seem otherworldly. With the help of his political contacts, Simić transformed the wild marshland into a nature reserve in 1997.

Three years later, Simić was at a fair in the nearby town of Ruma and saw some abused Balkan donkeys. No longer needed for work or transportation, they’d been beaten and were in bad shape. He had the idea to rescue them and bring them to Zasavica. Today, 180 Balkan donkeys, smaller than most donkeys and marked with crosses on their backs, roam the verdant marshland. Other native animals were added, including the Mangalica, related to the Hungarian “curly pig”, and the Podolian cow, originating from the European wild cow. Beavers were also reintroduced to the area.

“We lost contact with animals, and we need that contact,” Simić said.

But I’d come for the donkeys. More specifically, for the donkey milk cheese, which is the most expensive cheese in the world due to the extremely low milk yield of the magarica (female donkey): just 300 millilitres per day. Rich in vitamins and minerals, donkey milk is believed to slow down the aging process and has been used as an immunity booster in the Balkans since ancient times. Cleopatra allegedly even bathed in it. It is also purported to boost virility.

“If you drink our milk, you can even sleep with your own wife,” joked Simić, who has been married three times.

Simić had the notion to produce donkey milk cheese a few years ago.

“He is full of crazy ideas, but he is always right,” said farm manager Jovan Vukadinović, a formidable former traffic police chief with a near-white moustache that resembled a bristle brush.

No one had produced cheese from donkey milk

before, and it took some experimentation. Stevan Marinković, a dairy

technologist, was brought in to consult. Donkey milk doesn’t have enough

casein to make cheese, so he compensated by adding goat milk to the

mix. The winning formula, which Marinković is in the process of

patenting, turned out to be 60% donkey milk and 40% goat milk.

But despite there being no established rules for donkey milk (or donkey milk cheese) in Serbia, concerns arose over the use of unpasteurized milk, and Zasavica was forced to stop factory production of the cheese.

In the meantime, until official regulations are determined, local cheese makers Zoran Nedić, Momčilo Budimirović and his assistant, Milena, are producing small amounts of donkey cheese with milk pasteurized at low levels for Zasavica in a room adjacent to Budimirović’s kitchen in the nearby village of Glušci.

I sat at Budimirović’s dining table with Nedić, Vukadinović and Simić, who were chatting in rapid Serbian. Domaće crno vino (domestic red wine) and a wedge of white cheese were on the table.

“Is this donkey cheese?” I asked. Vukadinović shook his head. “Goat cheese, so you can taste the difference.” It was tangy and crumbly, with a dark kora od hrast (oak bark) rind.

Then, without much ceremony, Budimirović brought out a much smaller bell-shaped chunk of magareći sir (donkey cheese). It had a yellowish tinge, and was less crumbly than the goat cheese. This piece, the size of a cupcake, would sell for 50 euros, I was told. Nedić cut me a slice. Its flavour was sweet, clean and mild, unlike any cheese I had ever tasted.

We headed to the cheese room to see how it was made. That day, the trio of cheese makers were crafting goat cheese, but they explained donkey cheese is essentially made the same way – although the exact method is a secret. Rennet is added to the milk to help it coagulate, and the curds are strained and hand packed into moulds. The cheese stays in the mould for 24 hours, then it is removed and refrigerated in a large trailer cooler in Budimirović’s yard.

Zasavica also sells donkey milk cosmetics, such as donkey milk soap and anti-ageing face creams, which contain essential fatty acids and high levels of vitamin A; and donkey milk liqueur that tastes like milky Limoncello.

The reserve, which has been supported by international grants, is working to become self-sustaining. Selling animal products is part of that plan, as is camping: Zasavica was rated among the 100 best campsites in Europe in 2013 and 2014.

Just before I left, Vukadinović and I took a walk through the reserve. Donkeys grazed on shrubbery and frolicked in the grass. They nuzzled, cleaned each other and nursed. A grey donkey ambled toward me.

“She’s pregnant,” Vukadinović said. “A magarica can be pregnant for more than a year.”

I reached out and rubbed her forehead, fingering her coarse hair. She nuzzled my hand and leaned her body into mine. When we turned to leave she followed me, nudging for more attention.

“They are very intelligent and social,” Vukadinović said. He bent down and hugged her neck. “This is very good for the stress.”

We sat down at a picnic table for lunch. Sun illuminated the flat landscape, highlighting various shades of green – moss, pine, fern – against a clear blue sky. Frogs sang. A stork soared overhead, landing on her nest atop Zasavica’s 18m-high watchtower.

Vukadinović brought out a plate of cured meats: Mangalica sausage, speck and donkey sausage. I cringed a little. “Try it,” he urged, gesturing to the donkey sausage.

This was one of their products I had not planned to sample. “How do you choose which donkeys are made into sausage?” I said. He explained that male donkeys sometimes become interested in their daughters, and then “it’s sausage time for them.”

I speared a mottled slice with a toothpick. The fatty meat was tough and slightly gamey. Even eating an incestuous donkey felt wrong after communing with these gentle creatures – but Zasavica embraces the cycle of life, replete with its imperfections.

Here you can go back to a way of living that has all but disappeared, when people cured their own meats and made their own cheese. You can experience virgin nature. You can believe, even for a moment, the local legend: on this land there was too much sun from Christ, which forever marked the Balkan donkey with a cross pattern on its coat, running down its spine.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

“Rakia?” he said, offering me a shot of the strong Balkan brandy that is often drunk in the morning, even before coffee.

“Ne, hvala,” I replied, shaking my head and thanking him. Instead, I accepted a cup of thick Turkish coffee accompanied by a shot glass of donkey milk from Zasavica’s herd. It was my first time tasting the sweet milk; I was even more eager to try the donkey cheese, a delicacy I’d learned about a few years back when rumours swirled that Serbian tennis ace Novak Djokovic was buying up their entire stock for his restaurants. Although the rumours were untrue, they brought global attention to Zasavica – and Serbia.

Despite being a nature lover, Simić never set out to create a farm. Twenty years ago, the former MP-turned-conservationist remembered that he’d heard about some wetlands in west-central Serbia. His ex-wife’s parents, who lived in a nearby village, took him to see them.

“I fell in love immediately,” he said.

Zasavica, named after the river that runs through it, is located just 90km northwest of Belgrade, but the 1,825-hectare area was virtually undiscovered. The place is ripe for bird watching, and in the summer, hues are so vibrant they seem otherworldly. With the help of his political contacts, Simić transformed the wild marshland into a nature reserve in 1997.

Three years later, Simić was at a fair in the nearby town of Ruma and saw some abused Balkan donkeys. No longer needed for work or transportation, they’d been beaten and were in bad shape. He had the idea to rescue them and bring them to Zasavica. Today, 180 Balkan donkeys, smaller than most donkeys and marked with crosses on their backs, roam the verdant marshland. Other native animals were added, including the Mangalica, related to the Hungarian “curly pig”, and the Podolian cow, originating from the European wild cow. Beavers were also reintroduced to the area.

“We lost contact with animals, and we need that contact,” Simić said.

But I’d come for the donkeys. More specifically, for the donkey milk cheese, which is the most expensive cheese in the world due to the extremely low milk yield of the magarica (female donkey): just 300 millilitres per day. Rich in vitamins and minerals, donkey milk is believed to slow down the aging process and has been used as an immunity booster in the Balkans since ancient times. Cleopatra allegedly even bathed in it. It is also purported to boost virility.

“If you drink our milk, you can even sleep with your own wife,” joked Simić, who has been married three times.

Simić had the notion to produce donkey milk cheese a few years ago.

“He is full of crazy ideas, but he is always right,” said farm manager Jovan Vukadinović, a formidable former traffic police chief with a near-white moustache that resembled a bristle brush.

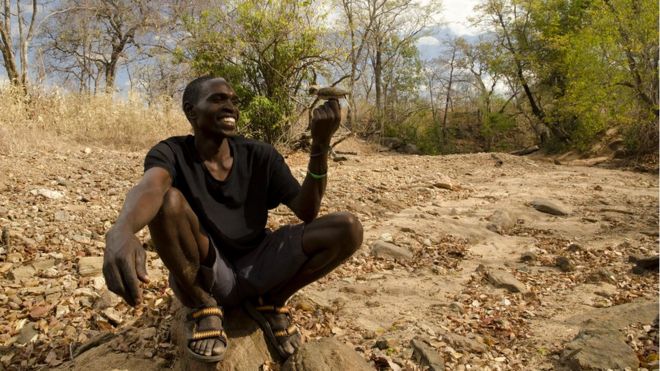

Donkey milk has been used as an immunity booster in the Balkans since ancient time (Credit: Kristin Vuković)

But despite there being no established rules for donkey milk (or donkey milk cheese) in Serbia, concerns arose over the use of unpasteurized milk, and Zasavica was forced to stop factory production of the cheese.

In the meantime, until official regulations are determined, local cheese makers Zoran Nedić, Momčilo Budimirović and his assistant, Milena, are producing small amounts of donkey cheese with milk pasteurized at low levels for Zasavica in a room adjacent to Budimirović’s kitchen in the nearby village of Glušci.

I sat at Budimirović’s dining table with Nedić, Vukadinović and Simić, who were chatting in rapid Serbian. Domaće crno vino (domestic red wine) and a wedge of white cheese were on the table.

“Is this donkey cheese?” I asked. Vukadinović shook his head. “Goat cheese, so you can taste the difference.” It was tangy and crumbly, with a dark kora od hrast (oak bark) rind.

Then, without much ceremony, Budimirović brought out a much smaller bell-shaped chunk of magareći sir (donkey cheese). It had a yellowish tinge, and was less crumbly than the goat cheese. This piece, the size of a cupcake, would sell for 50 euros, I was told. Nedić cut me a slice. Its flavour was sweet, clean and mild, unlike any cheese I had ever tasted.

We headed to the cheese room to see how it was made. That day, the trio of cheese makers were crafting goat cheese, but they explained donkey cheese is essentially made the same way – although the exact method is a secret. Rennet is added to the milk to help it coagulate, and the curds are strained and hand packed into moulds. The cheese stays in the mould for 24 hours, then it is removed and refrigerated in a large trailer cooler in Budimirović’s yard.

Zasavica also sells donkey milk cosmetics, such as donkey milk soap and anti-ageing face creams, which contain essential fatty acids and high levels of vitamin A; and donkey milk liqueur that tastes like milky Limoncello.

The reserve, which has been supported by international grants, is working to become self-sustaining. Selling animal products is part of that plan, as is camping: Zasavica was rated among the 100 best campsites in Europe in 2013 and 2014.

We made something in the middle of the nothing“We made something in the middle of the nothing,” Vukadinović said. “We always have to find new ways to survive. It’s easy when they say ‘sustainable tourism’, but it’s not easy. We want to be the best. We know we can’t change the world, we can’t change Serbia, but we always want to do just a little better than normal. That is our mission.”

Just before I left, Vukadinović and I took a walk through the reserve. Donkeys grazed on shrubbery and frolicked in the grass. They nuzzled, cleaned each other and nursed. A grey donkey ambled toward me.

“She’s pregnant,” Vukadinović said. “A magarica can be pregnant for more than a year.”

I reached out and rubbed her forehead, fingering her coarse hair. She nuzzled my hand and leaned her body into mine. When we turned to leave she followed me, nudging for more attention.

“They are very intelligent and social,” Vukadinović said. He bent down and hugged her neck. “This is very good for the stress.”

We sat down at a picnic table for lunch. Sun illuminated the flat landscape, highlighting various shades of green – moss, pine, fern – against a clear blue sky. Frogs sang. A stork soared overhead, landing on her nest atop Zasavica’s 18m-high watchtower.

Vukadinović brought out a plate of cured meats: Mangalica sausage, speck and donkey sausage. I cringed a little. “Try it,” he urged, gesturing to the donkey sausage.

This was one of their products I had not planned to sample. “How do you choose which donkeys are made into sausage?” I said. He explained that male donkeys sometimes become interested in their daughters, and then “it’s sausage time for them.”

I speared a mottled slice with a toothpick. The fatty meat was tough and slightly gamey. Even eating an incestuous donkey felt wrong after communing with these gentle creatures – but Zasavica embraces the cycle of life, replete with its imperfections.

Here you can go back to a way of living that has all but disappeared, when people cured their own meats and made their own cheese. You can experience virgin nature. You can believe, even for a moment, the local legend: on this land there was too much sun from Christ, which forever marked the Balkan donkey with a cross pattern on its coat, running down its spine.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.