Voyager 1 becomes first human-made object to leave solar system

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- Study: Voyager 1 left heliosphere around August 25, 2012

- Voyager 1 and 2 were launched in 1977, 16 days apart

- Voyager 1 is now the first mission to explore interstellar space

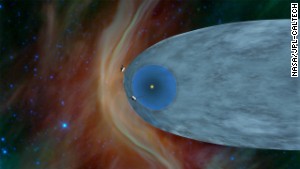

But scientists now have strong evidence that NASA's Voyager 1

probe has crossed this important border, making history as the first

human-made object to leave the heliosphere, the magnetic boundary

separating the solar system's sun, planets and solar wind from the rest

of the galaxy.

"In leaving the

heliosphere and setting sail on the cosmic seas between the stars,

Voyager has joined other historic journeys of exploration: The first

circumnavigation of the Earth, the first steps on the Moon," said Ed

Stone, chief scientist on the Voyager mission. "That's the kind of event

this is, as we leave behind our solar bubble."

A new study in the journal Science

suggests that the probe entered the interstellar medium around August

25, 2012. You may have heard other reports that Voyager 1 has made the

historic crossing before, but Thursday was the first time NASA announced

it.

NASA: Voyager 1 has left solar system

NASA: Voyager 1 has left solar system

Images from Voyager 2

Images from Voyager 2

The twin spacecraft Voyager 1 and 2 were launched in 1977, 16 days apart. As of Thursday, according to NASA's real-time odometer,

Voyager 1 is 18.8 billion kilometers (11.7 billion miles) from Earth.

Its sibling, Voyager 2, is 15.3 billion (9.5 billion) kilometers from

our planet.

Voyager 1 is being hailed

as the first probe to leave the solar system. But under a stricter

definition of "solar system," which includes the distant comets that

orbit the sun, we'd have to wait another 30,000 years for it to get that

far, Stone said.

Another milestone for long after we're gone: The probe will fly near a star in about 40,000 years, Stone said.

How do we know?

Voyager, currently

traveling at more than 38,000 miles per hour, never sent a postcard

saying "Greetings from interstellar space!" So whether it has made the

historic crossing or not is a matter of controversy.

"The spacecraft itself

really doesn't know," Stone said. "It's only instruments that can tell

us whether we're inside or outside."

Further complicating

matters, the device aboard Voyager 1 that measures plasma -- a state of

matter with charged particles -- broke in 1980.

To get around that,

scientists detected waves in the plasma around the spacecraft and used

that information to calculate density. Vibrations in the plasma came

from a large coronal mass ejection from the sun in 2012, resulting in

what Stone called a "solar wind tsunami." These vibrations reached the

area around Voyager this spring.

Measurements taken

between April 9 and May 22 of this year show that Voyager 1 was, at that

time, located in an area with an electron density of about 0.08 per

cubic centimeter.

This illustration shows NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft entering the space between stars.

In the interstellar

medium, the density of electrons is thought to be between 0.05 and 0.22

per cubic centimeter. The particles of interstellar plasma were created

by the explosions of giant stars, and carry the magnetic field of the

galaxy, scientists said.

Last year, between

October 23 and November 27, researchers calculate that Voyager 1 was in

an area with an electron density of 0.06 per cubic centimeter. That's

still within the interstellar space range, and it means that over time

the spacecraft passed through plasma with increasing electron density.

The study, led by

University of Iowa physicist Donald Gurnett, suggests that the plasma

density is about 30 times higher in the interstellar medium than in the

heliosphere, which is close to what scientists thought based on other

kinds of measurements. The boundary is called the heliopause.

When did it happen?

Scientists have been

using several kinds of measurements to figure out if and when Voyager 1

had reached the interstellar medium.

Evidence from particle

data had already pointed toward the conclusion that the probe succeeded.

In late July and early August of 2012, scientists saw dips in the

concentration of particles made in the solar system, and peaks in

particles made outside.

"If you just looked at

that data, you'd think it's pretty clear that we've actually crossed a

boundary. We're no longer in the place where the solar system particles

are being made, and we're actually out in the interstellar medium," said

Marc Swisdak, associate research scientist in the Institute for

Research in Electronics and Applied Physics at the University of

Maryland. Swisdak was not involved in the new study, but has worked with

Voyager data.

Magnetic field

measurements suggested otherwise. Researchers had expected to see stark

changes in magnetic field direction when the probe crossed out of the

heliosphere, but that wasn't supported by measurements from the probe.

Swisdak and colleagues

published a modeling study suggesting that the particle data is more

relevant, and that the magnetic field might not change as much as people

thought. They proposed a crossing-over date of July 27 -- about a month

sooner than the new study.

The specific date will

likely be debated for some time, Swisdak said. One possible explanation

is that if the heliosphere is analogous to an air-conditioned room,

Voyager stepped through the doorway into a hot room on July 27. For a

month it was in a metaphorical room with a mixture of hot and cold air,

and finally entered the truly hot part on August 25.

Puzzles still surround

the magnetic field at the edge of the heliosphere, Stone said, and

"We're going to be prepared to have more surprises."

What else is out there?

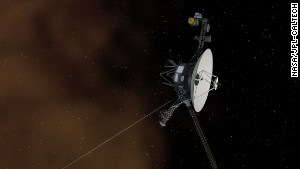

Voyager 1 has only 68 KB

of memory on board -- far less than a smartphone, said Suzanne Dodd,

Voyager project manager. Scientists communicate with the spacecraft

every day.

"It's the little spacecraft that could," she said in a NASA press conference.

The probe now has a totally new mission, Stone said.

"We're now on the first

mission to explore interstellar space," he said. "We will now look and

learn in detail how the wind which is outside, that came from these

other stars, is deflected around the heliosphere."

Wind -- made of

particles -- from these other stars has to go around the heliosphere the

way a water in a stream flows around a rock, Stone said. Scientists are

interested in learning more about the interaction between our solar

wind and wind from other stars.

Natural radioactive

decay provides heat that generates enough electricity to help Voyager 1

communicate with Earth. The first science instrument will be turned off

in 2020, and the last one will be shut down in 2025, Stone said.

Both Voyager probes carry time capsules known as "the golden record,"

a 12-inch, gold-plated copper disc with images and sounds so that

extraterrestrials could learn about us. Let's hope they can build

appropriate record players.

Voyager 2 will likely leave the heliosphere in about three to four years, Stone said.

Its plasma instrument is

still working, Stone said, so scientists can directly measure the

stellar wind's density, speed and temperature. That also means that when

it crosses out of the heliosphere, Voyager 2 will send a clearer

signal.

At that time, it will join its twin in the vast nothingness between stars that used to be beyond our reach.

Follow Elizabeth Landau on Twitter at @lizlandau and on Google+.

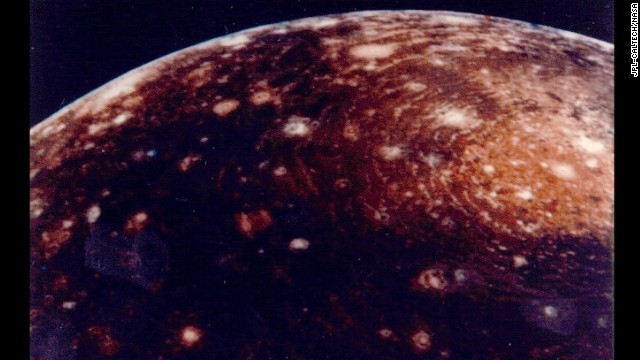

This image of

Jupiter's moon Callisto was captured from a distance of 350,000

kilometers. The large "bull's-eye" at the top of the image is believed

to be an impact basin formed early in Callisto's history. The bright

center of the basin is about 600 kilometers across and the outer ring is

about 2,600 kilometers across.

This image of

Jupiter's moon Callisto was captured from a distance of 350,000

kilometers. The large "bull's-eye" at the top of the image is believed

to be an impact basin formed early in Callisto's history. The bright

center of the basin is about 600 kilometers across and the outer ring is

about 2,600 kilometers across.

ไม่มีความคิดเห็น:

แสดงความคิดเห็น