Tourism boom threatens China's heritage sites

August 14, 2012 -- Updated 0706 GMT (1506 HKT)

Bristling with

battlements and turrets, the ornate towers were built by families and

villages in need of protection during the late 19th and early 20th

centuries when much of the country was controlled by warlords and

banditry was rife.

Now a UNESCO world heritage site, these days the Kaiping watchtowers, or diaolou as they are known locally, face a threat of a different nature -- the incredible boom in Chinese tourism.

The tiny village of Zili,

which has the largest collection of towers, attracts dozens of tour

buses on weekends. Their passengers are ushered around the towers by

guides sporting red flags and microphones rigged up to loud speakers.

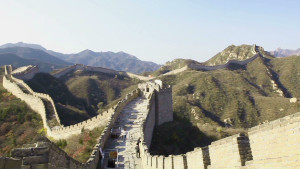

Explore the Great Wall of China

Sports car damages ancient Chinese site

They chase the skinny

chickens that roam about the dirt paths, snap photos, sample "peasant

family food" and buy rustic bamboo souvenirs, while the village's few

remaining elderly residents sit on small plastic stools and look on

bemused.

It's a scene that's

played out at other UNESCO sites across China, where world heritage

status is increasingly being used as a economic vehicle to develop

backward regions, says Chris Ryan, a professor of tourism at The

University of Waikato in New Zealand.

"The idea behind having

this status is that there are conservation, preservation and restoration

issues, where in China it seems to be primarily geared toward promoting

tourism and its economic benefit," says Ryan, who has studied Kaiping

and another world heritage site in Anhui province, eastern China.

According to Ryan,

Chinese made 2.6 billion trips last year, up from just over a billion

seven years ago and numbers are expected to rise further.

"Places that were

previously very remote and didn't see a lot of tourists are now seeing

enormous numbers arriving because they have the money to travel," says

Neville Agnew, group director of the Getty Conservation Institute, which

has worked in China since 1989.

"It's an interesting

phenomenon because it's in complete contrast to the experience in Egypt,

where almost all the visitors are foreigners."

People are getting richer and they have the right to appreciate heritage sites but we need a balance

Jing Feng, UNESCO

Jing Feng, UNESCO

China now has 43 world

heritage sites, the most of any country in the world. Dozens of other

wannabe UNESCO sites across China are preparing bids.

Jing Feng, the

Paris-based chief of UNESCO's Asia and Pacific section, says that the

prestige of world heritage inscription always means an increase in

visitor numbers but acknowledges the pressures of mass tourism in China

are particularly acute.

"People are getting richer and they have the right to appreciate heritage sites but we need a balance," he says.

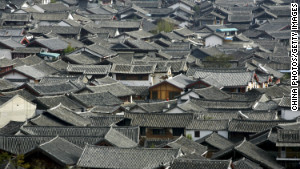

View of Lijiang in Yunnan province

Tackling the problem is

difficult. Jing singles out Lijiang, an ancient town set in a dramatic

mountain landscape in the southwestern province of Yunnan, as a place

that has struggled to accommodate a surge in tourists.

Designated a world

heritage site in 1997, the town, home to the matriarchal Dongba culture,

now receives 11 million visitors a year and conservation experts have

been shocked by the level of commercialization.

Locals have moved out of the city's ancient core, renting their homes out to businesses.

Jing was part of a

UNESCO monitoring mission to the town in 2008 and local authorities have

pledged to improve visitor management and shut the discos and karaoke

bars that had sprung up.

However, a doubling of admission ticket prices in a bid to reduce visitor numbers has had little impact and officials aim to increase visitor number to 16 million by 2015.

UNESCO has only twice

removed world heritage sites from its list and Jing says there is little

chance, for now at least, that any Chinese sites would lose the

designation because authorities had put forward "corrective measures."

Poor, rural areas

bypassed by China's recent economic boom are those most keen to secure

world heritage status, says Han Li, who works for the Global Heritage

Fund in China.

Local officials often

take out huge loans to build infrastructure to prepare their bid, she

says, and local people, at least, initially welcome the opportunity to

find work outside farming or as alternative to migration.

"Having world heritage

status definitely changes your property values, your investment

opportunities and it's a really big life-saver for a lot of these

places," she says.

It's important to remember that heritage does have its own inherent value and it's not just about a tangible financial return

Han Li, Global Heritage Fund

Han Li, Global Heritage Fund

Officials in charge of

Kaiping's watchtowers have said they aim to attract up to 2 million

visitors each year, up from 100,000 in 2007 when it was first inscribed

as a world heritage site with a view to generating revenues of 50

million yuan (US$7.8 million).

Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, northwest China

How this money will be spent will be key to the future of Kaiping's watchtowers.

So far, it appears that

much of the money generated has been spent on car parks, ticket booths

and landscaping in the four villages featured in tourist brochures.

It's not clear what will

happen to the hundreds of other towers not earmarked for tourist

development. They are used as barns and storage sheds or stand empty and

forlorn despite their protected status.

Many were abandoned

after the Communist victory in 1949 when those with overseas ties fled.

More recently, villagers have left for the booming factory towns on the

other side of the Pearl River Delta.

The challenge for the

local authorities in Kaiping, and at China's other heritage sites, is

how to manage tourists visits so that they bring maximum economic

benefit without harming the heritage sites and those who live nearby.

One radical solution is to limit visitor numbers.

For example, from next

year the Mogao Grottoes in remote Northwestern China plans to allow

6,000 visitors per day, down from up to 11,000 at present, says Agnew at

the Getty Conservation Institute.

The move follows fears

that the moisture from visitors' breath and sweat was harming the

centuries-old cave paintings and Buddhist sculptures.

But this approach is

unlikely to be adopted widely, especially at living sites such as

Lijiang's old town and Kaiping, where economic imperatives are most

likely to trump heritage preservation.

"World heritage sites don't need to be static -- they can bring income and development," says Li at the Global Heritage Fund.

"But I think it's

important to remember that heritage does have its own inherent value and

it's not just about a tangible financial return."

As developers clamour for land, Beijing has found it hard to protect its ancient lanes, also known as hutongs.

As developers clamour for land, Beijing has found it hard to protect its ancient lanes, also known as hutongs.

ไม่มีความคิดเห็น:

แสดงความคิดเห็น