Syrian president in spotlight after deadly attacks

July 19, 2012 -- Updated 0115 GMT (0915 HKT)

Bashar al-Assad vowed to lead Syria "towards a future that fulfills the hopes and legitimate ambitions of our people."

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- Al-Assad grew up in the shadow of his father, the late president Hafez al-Assad

- His father ruled with iron fist, jailing some dissidents and marginalizing others

- His son, Bashar, enjoyed rare privileges and education as he studied abroad

- But those in Europe and the U.S. initially seemed heartened by the incoming president

As the crisis unfolded, experts looked beyond the day's events to the roots of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's power for insights into the 16-month rebellion that grips the Middle Eastern nation.

Al-Assad grew up in the shadow of his father, President Hafez al-Assad, a Soviet ally who ruled Syria for three decades and helped propel a minority Alawite population to key political, social and military posts.

By most accounts, the elder al-Assad governed with an iron fist, forging a police state that quashed opposition by jailing dissidents and marginalizing other political groups.

Hafez al-Assad was born into a poor family and graduated from Ḥomṣ Military Academy as an air force pilot, before rising in Baath Party leadership and gaining power in the "Corrective Revolution" of 1970.

His son, Bashar, enjoyed rare privileges and education as he studied abroad, while his older son, Bassel, was the man groomed to succeed him and assume power.

But when Bassel died in a car crash in 1994, Bashar was thrust into the national spotlight and switched his university focus from medicine to military science.

"Dr. Bashar," who had headed the Syrian Computer Society, earned a degree in ophthalmology and enjoyed windsurfing, may have appeared an unlikely choice.

Explosion kills top Syrian officials

Explosion kills top Syrian officials  Clinton says Assad regime won't survive

Clinton says Assad regime won't survive  Russia not supporting al-Assad

Russia not supporting al-Assad  2005: Amanpour and Assad

2005: Amanpour and Assad

But many observers in Europe and the United States seemed heartened by the incoming president, who presented himself as a fresh, youthful leader who might usher in a more progressive, moderate regime.

Asma Akhras al-Assad, whom he married in 2000, is a former investment banker of Syrian descent who grew up in London.

When al-Assad's father died in June of that year, it took just hours for the Syrian parliament to amend the constitution and lower the presidential age of eligibility from 40 to 34, a move that allowed Bashar to succeed his father.

Within weeks, he was also made a member of the regional command for the ruling Baath Party, a requirement of succession.

"I shall try my very best to lead our country towards a future that fulfills the hopes and legitimate ambitions of our people," al-Assad said during his inauguration speech.

But Western hopes for a more moderate Syria sank when the new leader promptly maintained his country's traditional ties with militant groups, such as Hamas and Hezbollah.

Suspicions later surfaced among the country's regional neighbors over whether Syria was developing a covert nuclear program.

Meanwhile, al-Assad repeatedly vowed to stamp out corruption while strengthening his own grasp on power.

But in recent months -- and after more than a decade in power -- the Syrian leader has drawn criticism from around the globe as he's met popular protests and unrest with force.

Thousands have been killed and many more displaced as the conflict has unfolded, with state security forces firing on demonstrators, many of whom have joined opposition groups, including armed rebel brigades.

As pressure has mounted, the inner circle of the Syrian leader has became more of a family affair, said David Lesch, a professor of Middle East history and author of "The New Lion of Damascus: Bashar al-Assad and Modern Syria."

"That's part of what Bashar has been doing ever since he came to power," Lesch said. "He has put members of his extended family ... in various parts of government and military security apparatus. If the day came -- and it did come -- where there was a threat to the regime, he could count on the loyalty of those closest to him."

The president's family belongs to the country's minority Alawite sect, who are largely driven by fears that they could be overwhelmed should al-Assad lose power, according to the president's uncle Rifaat. Recent reports, however, suggest discontent even within the minority community over his handling of the crisis.

Al-Assad's youngest brother, Maher, is thought to be Syria's second-most powerful man, overseeing two of the army's strongest units: the Republican Guard, which protects the regime in Damascus, and the elite Fourth Armored Division, which suppressed the early uprisings in southern Syria.

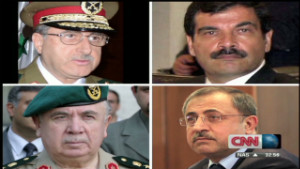

But on Wednesday, a rebel attack killed Defense Minister Dawood Rajiha; Deputy Defense Minister Assef Shawkat -- al-Assad's brother-in-law; and Hasan Turkmani, al-Assad's security adviser and assistant vice president, according to state television.

Shawkat was once in charge of the army's intelligence services and was said to be one of the president's closest allies.

Interior Minister Ibrahim al-Shaar was among those injured in the blast, state TV said, adding that he "is in good health and that his condition is stable."

Wednesday's attack occurred during a meeting of ministers and security officials and was coordinated by rebel brigades in Damascus, opposition groups say.

Al-Assad quickly named Gen. Fahd Jassem al-Freij as defense minister, according to the state-run news agency SANA.

State media also reported that authorities have killed or captured a "large number" of terrorist infiltrators in Damascus and inflicted "heavy losses" on terrorists in Homs and Idlib.

But video from a Damascus suburb showed Syrians rejoicing after news spread of the bombing.

Meanwhile, reports of deaths across the country occur almost every day, with a London-based opposition group reporting last week that government forces carried out a massacre in Hama province, killing 220 people there.

Al-Assad's administration has consistently said that its forces are targeting armed terrorists funded by outside agitators.

In early July, al-Assad told a German television station that a months-old peace plan aimed at ending the violence hasn't failed, but rather has yet to be implemented because foreign countries are supporting "terrorists."

Former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan, named as a special envoy to the region, has spearheaded the peace effort.

The president's remarks came on the same day that U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton held that the days for the Syrian regime are numbered.

Noting recent defections, Clinton said, "The sand is running out of the hourglass."

ไม่มีความคิดเห็น:

แสดงความคิดเห็น