Liberal Catholic Dorothy Day Considered for Sainthood

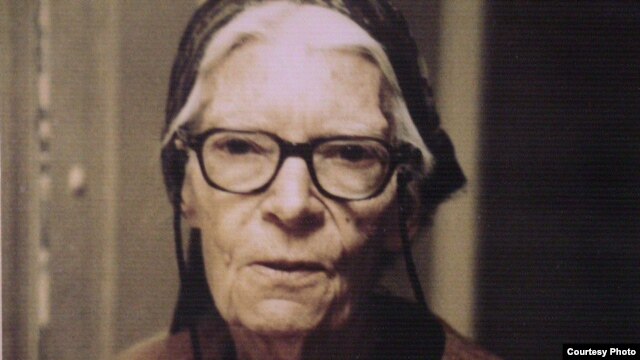

US bishops hope to have Dorothy Day, who died in 1980, declared a saint. (Marquette University Archives)

December 10, 2012

NEW YORK CITY — Dorothy Day is not a familiar name in the United States or around the world.

However, for about half of the 20th century, her name was synonymous with orthodox Catholic teachings on social justice and morality. U.S. bishops hope to have Day, who died in 1980, canonized.

Some Catholics see the bid to declare Day a saint as a political move to reconcile the conservative and liberal wings of the American Catholic Church.

Day did not always fit the common stereotype of a Catholic saint. In a 1973 interview, she offered a no-nonsense rationale for feeding the poor that is earthy, not ethereal.

“If your brother is hungry you feed him," she said. "You don’t meet him at the door and say ‘be thou filled’ or wait a couple of weeks and you’ll get a welfare check. You sit him down.”

Day was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1897 to a middle class Protestant family that rarely attended church. She became radicalized at an early age, says biographer Jim O’Grady, author of "Dorothy Day: With Love for the Poor."

“When she moved to New York in her late teens, she was around a lot of radical agitators. She wrote her left-wing periodicals. She was a friend of the labor movement and anti-war groups," O'Grady says. "She interviewed Trotsky when he passed through New York City. She did some heavy drinking with Eugene O’Neill in a saloon in Greenwich Village and at some point she had an abortion and a divorce. So that was her youth.”

In "The Long Loneliness," Day’s 1952 autobiography, she recounts a deep spiritual crisis, followed by a religious awakening which climaxed with the 1929 birth of her daughter, Tamar, who Day had baptized.

"The way she described it, she was so suffused with gratitude that she turned to God," O'Grady says. "She herself was baptized as a Catholic and she embarked on this lifelong journey of learning what that was. But she never stopped having this deep fervor for issues of social justice."

In 1933, during the Depression, Day and a fellow activist began publishing a newspaper called The Catholic Worker. Its headquarters in a poor New York neighborhood soon grew into a place where the homeless could always find shelter and the hungry could get a meal.

The movement spread. Today there are well over 100 Catholic Worker affiliates worldwide. Sister Mary Ann Walsh, spokesperson for the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, says it is these works of mercy which underlie efforts to canonize Day.

“Dorothy Day certainly was an extraordinary person who lived in voluntary poverty and spent her whole life serving the poor and that certainly that characterizes a saint," she says, "somebody who could be so selfless in their giving of themselves to others.”

However, Day often took positions which were at odds with the mainstream Catholic hierarchy. She advocated for the redistribution of wealth, for example, and fought for workers' rights. She was a pacifist, even during World War II, which nearly doomed The Catholic Worker.

Walsh acknowledges Day's priorities did not always coincide with those of church leaders.

“She was in the trenches," Walsh says. "She didn’t see her role in life as trying to lobby bishops, for example. She never craved the limelight in any way.”

Tom Cornell, who worked with Day for decades at The Catholic Worker, is certain she was a saint. He also believes efforts to canonize her now could be an effort by top church officials to bridge American Catholicism’s conservative and liberal wings.

He notes that some sainthood advocates emphasize only her path from leftist youth to Catholic convert, not her tireless work to organize unions, end war, and build housing and soup kitchens.

“I wouldn’t say I’m suspicious," Cornell says, "but The Catholic Worker gets a little upset when we see… no mention of the reason why these are needed [which is] because of the failure of our social and economic system, the failure of capitalism, the feeding on war, and making war necessary.”

Before Day can be declared a saint, there must be two proven miracles attributed to her intercession. It’s a bureaucratic process than can take decades to complete. Meanwhile, The Catholic Worker continues to publish.

However, for about half of the 20th century, her name was synonymous with orthodox Catholic teachings on social justice and morality. U.S. bishops hope to have Day, who died in 1980, canonized.

Some Catholics see the bid to declare Day a saint as a political move to reconcile the conservative and liberal wings of the American Catholic Church.

Day did not always fit the common stereotype of a Catholic saint. In a 1973 interview, she offered a no-nonsense rationale for feeding the poor that is earthy, not ethereal.

“If your brother is hungry you feed him," she said. "You don’t meet him at the door and say ‘be thou filled’ or wait a couple of weeks and you’ll get a welfare check. You sit him down.”

Day was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1897 to a middle class Protestant family that rarely attended church. She became radicalized at an early age, says biographer Jim O’Grady, author of "Dorothy Day: With Love for the Poor."

“When she moved to New York in her late teens, she was around a lot of radical agitators. She wrote her left-wing periodicals. She was a friend of the labor movement and anti-war groups," O'Grady says. "She interviewed Trotsky when he passed through New York City. She did some heavy drinking with Eugene O’Neill in a saloon in Greenwich Village and at some point she had an abortion and a divorce. So that was her youth.”

In "The Long Loneliness," Day’s 1952 autobiography, she recounts a deep spiritual crisis, followed by a religious awakening which climaxed with the 1929 birth of her daughter, Tamar, who Day had baptized.

"The way she described it, she was so suffused with gratitude that she turned to God," O'Grady says. "She herself was baptized as a Catholic and she embarked on this lifelong journey of learning what that was. But she never stopped having this deep fervor for issues of social justice."

In 1933, during the Depression, Day and a fellow activist began publishing a newspaper called The Catholic Worker. Its headquarters in a poor New York neighborhood soon grew into a place where the homeless could always find shelter and the hungry could get a meal.

The movement spread. Today there are well over 100 Catholic Worker affiliates worldwide. Sister Mary Ann Walsh, spokesperson for the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, says it is these works of mercy which underlie efforts to canonize Day.

“Dorothy Day certainly was an extraordinary person who lived in voluntary poverty and spent her whole life serving the poor and that certainly that characterizes a saint," she says, "somebody who could be so selfless in their giving of themselves to others.”

However, Day often took positions which were at odds with the mainstream Catholic hierarchy. She advocated for the redistribution of wealth, for example, and fought for workers' rights. She was a pacifist, even during World War II, which nearly doomed The Catholic Worker.

Walsh acknowledges Day's priorities did not always coincide with those of church leaders.

“She was in the trenches," Walsh says. "She didn’t see her role in life as trying to lobby bishops, for example. She never craved the limelight in any way.”

Tom Cornell, who worked with Day for decades at The Catholic Worker, is certain she was a saint. He also believes efforts to canonize her now could be an effort by top church officials to bridge American Catholicism’s conservative and liberal wings.

He notes that some sainthood advocates emphasize only her path from leftist youth to Catholic convert, not her tireless work to organize unions, end war, and build housing and soup kitchens.

“I wouldn’t say I’m suspicious," Cornell says, "but The Catholic Worker gets a little upset when we see… no mention of the reason why these are needed [which is] because of the failure of our social and economic system, the failure of capitalism, the feeding on war, and making war necessary.”

Before Day can be declared a saint, there must be two proven miracles attributed to her intercession. It’s a bureaucratic process than can take decades to complete. Meanwhile, The Catholic Worker continues to publish.

ไม่มีความคิดเห็น:

แสดงความคิดเห็น