Analysis: Why Romney lost

November 7, 2012 -- Updated 2248 GMT (0648 HKT)

Romney: Election over, principles endure

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- Some Republicans blame Sandy, stances on social issues for Romney loss

- Others say Obama's ground game was underestimated

- Loss of young, minority voters is sign party may be out of touch with fast-growing demographics

- Former GOP chairman questions whether Paul Ryan was best running mate pick

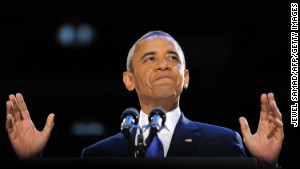

When it became clear

about midnight that President Barack Obama was safely on the way to

re-election, a handful of cranky and inebriated Republican donors

wandered about Romney's election night headquarters, angrily demanding

that the giant television screens inside the ballroom be switched from

CNN to Fox News, where Republican strategist Karl Rove was making

frantic, face-saving pronouncements about how Ohio was not yet lost.

Rove was wrong, of course.

But the signs of

desperation inside the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center on

Tuesday night were symptomatic of a Republican Party now standing at a

crossroads, with not much track in sight.

2 men, 2 speeches, 1 message

2 men, 2 speeches, 1 message

A six-year road to defeat for Romney

A six-year road to defeat for Romney

See the president's full victory speech

See the president's full victory speech

How did Romney lose a race that seemed so tantalizingly within reach just one week ago?

"We were this close," one of Romney's most senior advisers sighed after watching the Republican nominee concede. "This close."

Little support from young, minorities

Some answers are easy.

Romney lost

embarrassingly among young people, African-Americans and Hispanics, a

brutal reminder for Republicans that their party is ideologically out of

tune with fast-growing segments of the population.

Obama crushed Romney

among Hispanic voters by a whopping 44 points, a margin of victory that

likely propelled the president to victories in Nevada, Colorado and

possibly Florida.

The stunning defeat

alarmed Republicans who fear extinction unless the party can figure out

how to temper the kind of hardline immigration rhetoric that Romney

delivered during his Republican primary bid.

"Latinos were

disillusioned with Barack Obama, but they are absolutely terrified by

the idea of Mitt Romney," said GOP fundraiser Ana Navarro, a confidante

to former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush and Sen. Marco Rubio.

Sandy upsets campaign 'momentum'

Beyond the ugly math

staring them in the face, Romney's top aides and the Republican

heavyweights who populated the somber ballroom Tuesday evening offered

an array of explanations for their loss.

With some of them

double-fisting beers and others sipping bourbon, members of Romney's

team blamed several factors that were, in some ways, beyond their

control.

Many campaign aides

pointed the finger at Sandy, the punishing superstorm and October

surprise that razed the East Coast and consumed news coverage for what

was supposed to be the final full week of campaigning.

It upset the dynamic of a

campaign that had been reset during the first debate in Denver, where

Obama delivered a wilting-flower act in full view of the American

populace that allowed Romney to seize control of the race and set the

terms for the final fall sprint.

The storm, former Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour told CNN on Sunday, "broke Romney's momentum."

After being criticized

in the media for focusing on "small things" like Big Bird and

"Romnesia," Sandy offered Obama a chance to once again look

presidential.

There also are very real

hard feelings inside the Romney camp about the way New Jersey Gov.

Chris Christie, a Republican, seemed to lavish praise on Obama in the

wake of Sandy's destruction, allowing Obama to appear bipartisan just as

Romney was attacking him for being petty and partisan.

"He didn't have to bear hug the guy," complained one Romney insider.

"It won't be forgotten easily," grumbled another about Christie.

Social conservatives blame squishy positions

As Romney aides began

the soul-searching that usually follows a loss, Republicans outside the

campaign began pointing fingers at the team.

Some social

conservatives were quick to rip open barely healed wounds, claiming that

Romney's squishy positions on abortion and same-sex marriage -- closely

scrutinized during both of his Republican primary campaigns -- left

grass-roots Republicans uninspired.

"What was presented as

discipline by the Romney campaign by staying on one message, the

economy, was a strategic error that resulted in a winning margin of

pro-life votes being left on the table," said Marjorie Dannenfelser,

president of the anti-abortion Susan B. Anthony List.

Some wondered aloud

about the selection of Rep. Paul Ryan of Wisconsin as Romney's running

mate, suggesting that a Republican from a more winnable battleground

state might have made a difference.

"Rob Portman would've

been worth 1% in Ohio," said former Ohio GOP Chairman Kevin DeWine.

"Marco Rubio would've been worth a point in Florida. Bob McDonnell

would've been worth a point in Virginia."

The Romney team and his

super PAC allies, some Republicans are already saying, ran a banal

series of television ads and allowed their candidate to be defined early

on by Obama as an outsourcing plutocrat who wanted to let Detroit go

bankrupt.

Their pushback seemed

feeble for most of the summer and early autumn. And crucially, Romney

never seemed to articulate a clear rationale for the presidency.

The campaign's decision

to air a misleading ad in Toledo media market about Chrysler moving Jeep

production to China during the closing days of the race is also

emerging as a prime reason for Romney's loss in the state he needed to

win most.

One senior Ohio

Republican called the Jeep ad a "desperate" move and said the Romney

campaign walked into a "hornet's nest" of negative press coverage.

Nick Everhart, a Columbus-based ad maker, blamed the Ohio loss, in part, on the Romney campaign's "poor media buying."

But an adviser to one

prominent Republican governor who campaigned for Romney said the

campaign's problems were more fundamental.

"Obama ran a very smart

but very small campaign, which he could afford to do because he was

running against a very small opponent," this Republican said. "The

fundamentals of the election were the same all along, and they were

this: When there's an incumbent no one wants to vote for, and a

challenger that no one wants to vote for, people will vote for the

incumbent. At no point did Romney give people any reason to vote for

him, and so they didn't."

Democrats' strong ground game

Romney may never have

been the GOP's dream candidate, but even if he were, Republicans would

still have been forced to confront another troubling structural problem

on Election Day.

Democrats showed

decisively that their ground game -- the combined effort to find,

persuade and turn out voters -- is devastatingly better than anything

their rivals have to offer.

In 2004, Republicans tapped the science of microtargeting to redefine campaigns. That is now ancient history.

"When it comes to the

use of voter data and analytics, the two sides appear to be as unmatched

as they have ever been on a specific electioneering tactic in the

modern campaign era," Sasha Issenberg, a journalist and an expert in the

science of campaigning, wrote just days before the election proved him

right. "No party ever has ever had such a durable structural advantage

over the other on polling, making television ads, or fundraising, for

example."

The Romney campaign and

the Republican National Committee entered Election Day boasting about

the millions of voter contacts -- door knocks and phone calls -- they

had made in all the key states.

Volunteers were making

the calls using an automated VOIP-system, allowing them to dial

registered voters at a rapid clip and punch in basic data about them on

each phone's keypad, feeding basic information into the campaign's voter

file.

But volunteer callers

were met with angry hang-ups and answering machines just as much as

actual voters on the other end of the line. It was a voter contact

system that favored quantity over quality.

At the same time, the campaign's door-to-door canvassing effort was heavily reliant on fired-up but untrained volunteers.

Obama organizers,

meanwhile, had been deeply embedded in small towns and big cities for

years, focusing their persuasion efforts on person-to-person contact.

The more nuanced data

they collected, often with handwritten notes attached, were synced

nightly with their prized voter database in Chicago.

After the dust had

cleared, the GOP field operation, which had derided the Obama operation

and gambled on organic Republican enthusiasm to push them over the top,

seemed built on a house of cards.

"Their deal was much

more real than I expected," one top Republican with close ties to the

Romney campaign said of the Obama field team.

Sources involved in the

GOP turnout effort admitted they were badly outmatched in the field by

an Obama get-out-the-vote operation that lived up to their immense hype

-- except, perhaps, in North Carolina, where Romney was able to pull out

a win and Republicans swept to power across the state.

Multiple Romney advisers

were left agog at the turnout ninjutsu performed by the Obama campaign,

both in early voting and on Election Day.

Not only did Obama field

marshals get their targeted supporters to the polls, they found new

voters and even outperformed their watershed 2008 showings in some

decisive counties, a remarkable feat in a race that was supposed to see

dampened Democratic turnout.

In Florida's

Hillsborough County, home to Tampa, the Obama campaign outpaced their

final 2008 tally by almost 6,000 votes. In Nevada's vote-rich Clark

County, Obama forces scrounged up almost 9,000 more votes than they did

four years ago.

Tuesday's outcome laid

bare this truth: The two campaigns placed very different bets on the

nature of the 2012 electorate, and the Obama campaign won decisively.

Romney officials had

modeled an electorate that looked something like a mix of 2004 and 2008,

only this time, Democratic turnout would be depressed, and the most

motivated voters would be whites, seniors, Republicans and independents.

Heading into Election

Day, the Romney campaign's final set of internal poll numbers showed

their candidate with a 6-point lead in New Hampshire, a 3-point lead in

Colorado, a 2-point lead in Iowa, a 3-point lead in Florida and near

ties in Virginia and Pennsylvania.

Ohio was their biggest

problem. According to the campaign's internal polls obtained by CNN,

Romney was trailing in the must-win state by a full 5 points on the

Sunday before the election, the last day of tracking.

Officials in Boston

dispatched Romney for a pair of 11th-hour campaign stops in Cleveland

and Pittsburgh, a show of Election Day vitality and confidence that was,

in reality, a last-ditch attempt to move the needle with just hours

until the polls closed.

The Obama campaign was of a different mindset.

Late last month, a few

days before Halloween, four members of Obama's senior campaign staff --

deputy campaign manager Stephanie Cutter, pollster Joel Benenson,

battleground state director Mitch Stewart and press secretary Ben LaBolt

-- flew from Chicago to Washington to brief reporters on the state of

the race.

With the president's

campaign on the ropes in the wake of his awful debate performance in

Denver, the quartet had a straightforward, math-driven sales pitch.

The share of the

national white vote would decline as it has steadily in every election

since 1992. There would be modest upticks in Hispanic and

African-American voter registration, shifts that would overwhelmingly

favor the president. And Obama's get-out-the-vote operation was vastly

more sophisticated than the one being run by Romney and the Republican

National Committee.

On Monday, the night

before the election, the Obama campaign was optimistic their vision

would pan out. A relaxed group of about 60 campaign staffers including

campaign manager Jim Messina decamped to Houlihan's, just up the street

from their Chicago headquarters on Michigan Avenue, to drink beers and

take in Obama's final speech in Des Moines on C-SPAN.

The following morning,

bagels were delivered to headquarters for breakfast. Pizza was on the

menu for dinner. Some staffers in the in the campaign's press wing

turned on the Oxygen channel to watch a marathon of "America's Next Top

Model" -- a "mindless escape," in the words of one campaign operative.

When the results started flowing in, each chapter appeared to unfold as

planned.

The office burst into

loud cheers when Pennsylvania and Wisconsin turned blue early in the

evening, two very large pieces of mortar in a growing electoral

roadblock for Romney.

And when Ohio was called

for the president, the year-long avalanche of G-chats, e-mails and text

messages between reporters and campaign sources fell silent as

Obama-world closed ranks to celebrate their hard-won -- and meticulously

planned -- victory.

ไม่มีความคิดเห็น:

แสดงความคิดเห็น