Radical planes take shape

HIDE CAPTION

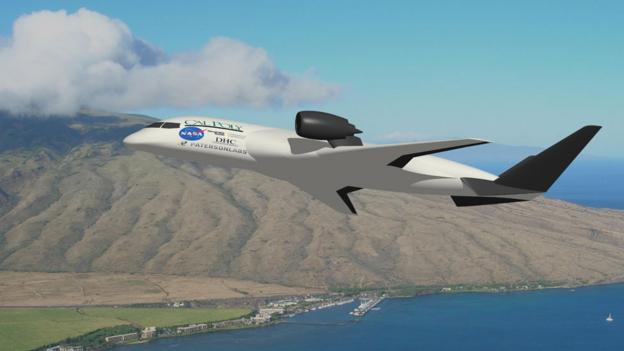

- Flying high

- Researchers are working to develop the next generation of green, commercial airliners that aim to reduce pollution, noise and fuel use. (Copyright: Nasa/Boeing)

Engineers and designers are giving commercial aircraft a makeover, in a bid to make them faster, greener and more efficient.

Look

up into the skies today at a passing aeroplane and the view is not that

much different to the one you would have seen 60 years ago. Then and

now, most airliners have two wings, a cigar-shaped fuselage and a trio

of vertical and horizontal stabilizers at the tail. If it isn’t broke,

the mantra has been, why fix it, particularly when your design needs to

travel through the air at several hundred miles an hour packed with

people.

But that conservative view could soon change. Rising fuel prices, increasingly stringent pollution limits, as well as a surge in demand for air travel, mean plane designers are going back to their drawing boards. And, now, radical new shapes and engine technologies are beginning to emerge, promising the biggest shake-up in air travel since de Haviland introduced the first commercial jet airliner in 1952.

Of course, it would be wrong to say nothing has changed in the last few decades, says Rich Wahls, an aerodynamicist at Nasa’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. “New model airliners don’t come out every year like cars, but it’s not as if they haven’t been evolving under the skin the whole time. There’s so much more technology in there nowadays.”

Earlier improvements went mostly unnoticed because they focused on building better and quieter turbine engines with higher performance and improved fuel consumption. There have also been huge strides in computer controls and fly-by-wire systems, which make a big difference to the pilot, but not to the passengers. And in recent years, the biggest development has been the use of strong, but lightweight plastics and composite materials rather than metals, reducing the weight of planes and the amount of fuel they need to burn. This has also allowed the development of “radical” new planes like the giant Airbus A380 and the Boeing Dreamliner.

But despite these advances, aviation engineers know there is still much to be done. Take fuel prices, for instance, which have soared in recent years. Despite modern planes being 60% to 70% more efficient than those built 60 years ago, aviation fuel expenditures now account for a quarter of an airlines operating expenses, placing them on a par with labor costs. In 2011, large US air carriers paid half again as much for fuel as what they paid in 2000. Add the fact that global airline travel is expected to grow to 3.3 billion annually by 2014 (up one third from 2009), and it’s clear why engineers are searching for new ways to boost performance.

Shock test

One of the biggest efforts to rethink the airplane is being conducted by Nasa’s Subsonic Fixed-Wing program, a collaboration between the US aerospace agency and industrial partners including Boeing, GE, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman and Pratt & Whitney, as well as academic institutions such as Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “We’re looking to see if we can develop technologies that can get us yet another 60 to 70% improvement in fuel efficiency,” says Wahls. In addition, the project wants to engineer new designs with a 71-decibel decrease in noise emissions and a four-fifths fall in nitrogen oxide pollutants from current standards. And, if these kinds of goals weren’t already aggressive enough, the team wants any new technology to enter service between 2030 and 2035 - a mere blink of an eye in an industry in which commercial aircraft can have multi-decade life spans.

“We are trying to determine which technologies are worth pursuing; those that might get us anywhere near our goals,” says Wahls’ boss, Ruben Del Rosario, subsonic fixed-wing program manager.

Planes under investigation by Nasa range from the extreme to the slightly more conventional. For example, Boeing’s Sugar Volt is a design that came about as part of the manufacturers Subsonic Ultra Green Aircraft Research (Sugar) project. The design – like many new concepts - is based around the idea of maximizing the plane’s lift. This reduces the amount of power needed to keep the plane in the air, as well as the amount of fuel it must burn.

But that conservative view could soon change. Rising fuel prices, increasingly stringent pollution limits, as well as a surge in demand for air travel, mean plane designers are going back to their drawing boards. And, now, radical new shapes and engine technologies are beginning to emerge, promising the biggest shake-up in air travel since de Haviland introduced the first commercial jet airliner in 1952.

Of course, it would be wrong to say nothing has changed in the last few decades, says Rich Wahls, an aerodynamicist at Nasa’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. “New model airliners don’t come out every year like cars, but it’s not as if they haven’t been evolving under the skin the whole time. There’s so much more technology in there nowadays.”

Earlier improvements went mostly unnoticed because they focused on building better and quieter turbine engines with higher performance and improved fuel consumption. There have also been huge strides in computer controls and fly-by-wire systems, which make a big difference to the pilot, but not to the passengers. And in recent years, the biggest development has been the use of strong, but lightweight plastics and composite materials rather than metals, reducing the weight of planes and the amount of fuel they need to burn. This has also allowed the development of “radical” new planes like the giant Airbus A380 and the Boeing Dreamliner.

But despite these advances, aviation engineers know there is still much to be done. Take fuel prices, for instance, which have soared in recent years. Despite modern planes being 60% to 70% more efficient than those built 60 years ago, aviation fuel expenditures now account for a quarter of an airlines operating expenses, placing them on a par with labor costs. In 2011, large US air carriers paid half again as much for fuel as what they paid in 2000. Add the fact that global airline travel is expected to grow to 3.3 billion annually by 2014 (up one third from 2009), and it’s clear why engineers are searching for new ways to boost performance.

Shock test

One of the biggest efforts to rethink the airplane is being conducted by Nasa’s Subsonic Fixed-Wing program, a collaboration between the US aerospace agency and industrial partners including Boeing, GE, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman and Pratt & Whitney, as well as academic institutions such as Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “We’re looking to see if we can develop technologies that can get us yet another 60 to 70% improvement in fuel efficiency,” says Wahls. In addition, the project wants to engineer new designs with a 71-decibel decrease in noise emissions and a four-fifths fall in nitrogen oxide pollutants from current standards. And, if these kinds of goals weren’t already aggressive enough, the team wants any new technology to enter service between 2030 and 2035 - a mere blink of an eye in an industry in which commercial aircraft can have multi-decade life spans.

“We are trying to determine which technologies are worth pursuing; those that might get us anywhere near our goals,” says Wahls’ boss, Ruben Del Rosario, subsonic fixed-wing program manager.

Planes under investigation by Nasa range from the extreme to the slightly more conventional. For example, Boeing’s Sugar Volt is a design that came about as part of the manufacturers Subsonic Ultra Green Aircraft Research (Sugar) project. The design – like many new concepts - is based around the idea of maximizing the plane’s lift. This reduces the amount of power needed to keep the plane in the air, as well as the amount of fuel it must burn.

ไม่มีความคิดเห็น:

แสดงความคิดเห็น